The use of agency nursing is exploding

According to a recent article in the Globe and Mail, 78 Ontario hospitals used private agency nurses last year, compared with 31 in 2020-21.

Private agency nurses are not unionized and receive no benefits or pension.

Agencies charge an average of $140 an hour for the services of a qualified nurse.

The highest hourly wage for a salaried nurse with seniority is around $50 an hour. According to economist Armine Yalnizyan in a commentary for the Toronto Star, agencies throwing money at private nursing agencies is very expensive. “Costs to the public purse have more than quadrupled, to 174 million dollars from 38 million dollars,” wrote Yalnizyan.

“They are parachuted in and don’t know the patients or where anything is. This means we have to train them, knowing that they earn a lot more money than we do, and that they’re just going to take off. It’s not fair to the patients or the staff.”

A Montreal nurse

The Ontario Nurses’ Association (ONA) provided the Globe and Mail with new data on the use of private nursing agencies over the past three years.

Gouging

The 78 hospitals covered by ONA’s data spent more than $168.3 million in taxpayer dollars on for-profit nursing agencies in the first three quarters of 2022 — that’s a 341% increase over the $38.1 million hospitals spent on private agency nurses in all of 2020-21.

Use of private agency staff is not limited to hospitals in Ontario. Private agency staff is increasingly showing up to work in the long-term care industry. In February, AdvantAge Ontario, which speaks for non-profit nursing homes, released a survey that found its members were being “gouged” by “predatory temporary staffing agencies.”

Nurses voice their displeasure

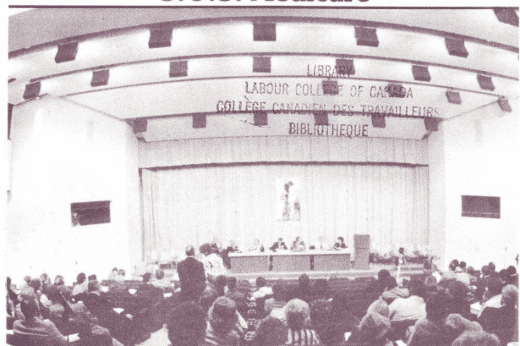

In June, during a rousing speech at the first convention of the Canadian Federation of Nurses Unions (CFNU) since the onset of the pandemic, CFNU President Linda Silas told the 1,100 delegates:

Nurses are working harder and working longer. Overtime hours hit a new high last summer.

Double shifts and cancelled vacations have become your everyday reality. And there’s no relief in sight for this summer. Meanwhile, governments have turned, more and more, to agency nurses.

In just four years we’ve seen up to a 550% increase in spending on agency nurses. Siphoning public funds into private pockets. Pulling more nurses out of the public system.”

“Nurses have not disappeared in some kind of cosmic rapture,” Alan Drummond, an emergency physician in Perth, Ontario, told the Globe and Mail.

Drummond’s rural hospital is relying on temporary nurses – many of whom are living in hotels – to keep its emergency department open this summer. They are expressing their dissatisfaction, saying: “There’s no future there.”

As part of contract negotiations that led to arbitration, ONA asked the Ontario Hospital Association to disclose the scale of use of private agency nurses.

Arbitrator William Kaplan stated in his decision that “the vast expansion in the use of overtime and agency nurses – demonstrated by truly astonishing growth in both cases – creates a real recruitment and retention problem” for hospitals. The decision awarded ONA nurses an average pay rise of 11% over two years.

Last summer, the Ontario Health Coalition, which represents 500 organizations, denounced the same problem.

In April, Québec passed a law banning the use of private recruitment agencies in the health care system by the end of 2025.

The long-term goal is to completely ban the use of for-profit nursing agencies by December 2024 in cities such as Québec City and Montreal, and by December 2025 in the rest of the province.

The use of for-profit nursing agencies cost the Québec public system $960 million in 2022, an increase of 380% compared with 2016, according to data from the Ministry of Health.

This represents 14.8 million hours worked, compared with 4.8 million six years ago, according to the Montreal Gazette.

The new law will set out the conditions under which the health care sector can use for-profit agencies, with fines of up to $150,000 for non-compliance.

Québec Health Minister Christian Dubé has said around 30,000 healthcare workers leave the public sector every year, including 10,000 who retire. Dubé hopes good collective agreements will be negotiated with the unions to retain the other 20,000 workers who leave for other reasons.

Agency nurses are well known, but less well known are agency orderlies, agency educators, agency occupational therapists, agency social workers and so on. All of them are growing rapidly in the Québec health care network.

“They are parachuted in and don’t know the patients or where anything is,” said a Montreal nurse, speaking on condition of anonymity. “This means that we have to train them, knowing that they earn a lot more money than we do, and that they will simply fly away. It’s not fair to the patients or the staff.”

CFNU, a member of the Canadian Health Coalition, has a very clear position on this situation. CFNU recommends:

- The federal government work with the provinces and territories to determine spending on private nursing agencies, including disclosure of total dollars spent, average wage rate, number of nurses, change in wages over the past five years, and how this compares across health care sectors, including hospitals, long-term care and home care.

- The federal government work with the provinces and territories to investigate and determine what Canadians receive in return for the money spent on agency nurses.

- The federal government work with the provinces and territories to limit the amount hospitals can spend on agency nurses.