It’s about more than just money, part XI

This is the eleventh part of a series examining the policy barriers and solutions to reducing surgical wait times in Canada. The series has been adapted from a research paper by Andrew Longhurst. The complete paper with reference list for the footnotes is available here.

While there is no question that governments must prioritize system improvements to reduce surgical wait times, continued investments in both acute care capacity and seniors’ care are also needed. The need for significant new spending on acute care capacity largely depends on the extent of improving how surgical care is delivered as well as investment in seniors’ home and community care.

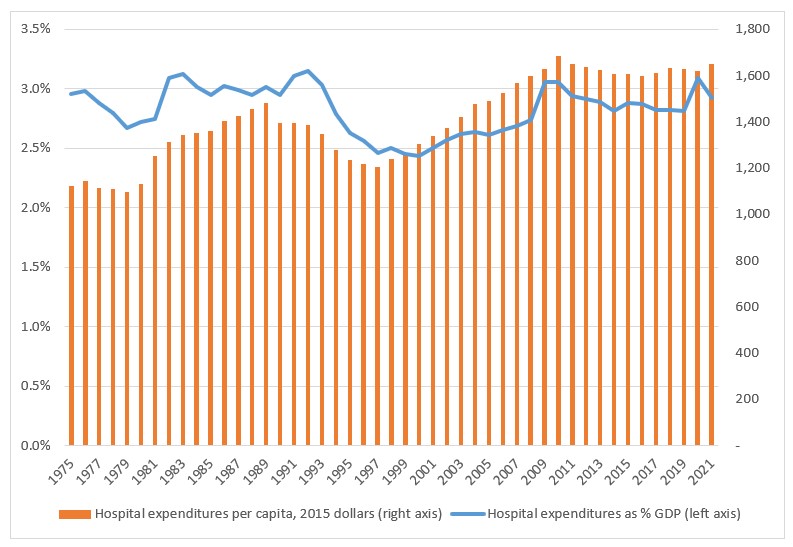

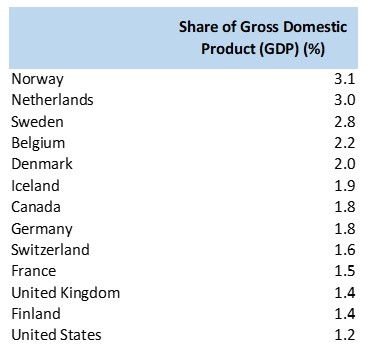

Canada is near the OECD per-capita average ($1,726) for public-sector hospital spending at $1,615 per capita (2019).[1] Even in the years prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, per capita hospital spending was rising, and hospital spending as a share of the economy (GDP) has generally remained stable in the last ten years (Figure 4). However, Canada spends less as a share of GDP on public long-term care compared to other similar high-income countries with publicly financed health systems (Figure 5). Long-term care is recognized to help reduce the problem of ALC and hospital crowding, and investment in this part of the health system can, in turn, help reduce surgical wait times. Comparative national-level data for home care and primary care – important in helping reduce pressures on acute hospital services—are not readily available.

Figure 4: Public-sector hospital expenditures in Canada, 1975 to 2021

Source: Author’s calculations using CIHI (2022a) Table C.3.1 and Appendices A, B, D.

Figure 5: Publicly funded long-term care spending as share of GDP in Canada and selected OECD countries, 2020

Source: OECD, 2022b

Federal health care funding: please attach strings (or chains)

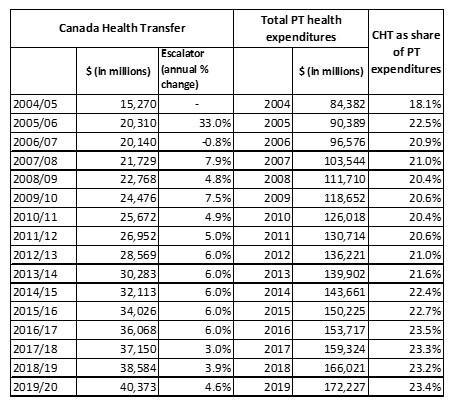

The Canada Health Transfer (CHT) is the single largest federal transfer payment to the provinces. When public health care was established in Canada, it was based on the premise that there would be 50%-50% cost-sharing between federal and provincial governments. But over the years, federal contributions have significantly diminished. In 2019/20, the federal government contributed 23.4 per cent of total public health care costs through the CHT.[2] To be fair, and as the federal government states, this distribution of funding does not account for the federal government transferring tax points to the provinces, which allowed the provinces to increase their ability to raise revenues.

The current federal Liberal government maintained the revised CHT funding formula established by the former Conservative government, resulted in reduced health funding.[3] In 2016/17, the federal government negotiated bilateral agreements with each of the provinces that set the CHT escalator (i.e., annual increase) at nominal GDP growth (with a floor of 3 per cent), plus an additional $11.5 billion in total of targeted funding for mental health and home care.[4] This was below the 5.2 per cent escalator that was needed to maintain existing services as recommended by provincial governments, the CCPA, the Canadian Health Coalition, and the Parliamentary Budget Office, among others. As Table 6 shows, the CHT escalator fell below 6 per cent after 2016/17. Even with the additional $11.5 billion targeted for mental health and home care, the bilateral agreements were estimated in 2017 to leave provinces with an shortfall of $31 billion over ten years (2016/17 to 2026/27).[5]

The recently negotiated federal health funding deal builds on significant targeted health transfers (referred to as CHT top-ups) in response to the pandemic and surgical backlogs of $500 million in 2019/20 and $4 billion in 2020/21.[6] Announced in February 2023, the new federal deal will provide provinces with $46.2 billion in new funding over 10 years through an increased CHT (guaranteed at 5 per cent annually for bilateral deals with the provinces. It also provides a personal support worker wage top-up. In total, only 58 percent of the total 10-year funding deal has strings attached.[7] Notably, the large provinces – Ontario, Quebec, and BC – will be required to spend much less of what they receive on health care, ranging from $0.54 to $0.57 of every dollar they receive.

Federal funding – whether through the CHT or bilateral deals – should be used to hold provinces accountable and require system improvement. At a minimum, these funds must actually fund health services, not be used to pad surpluses or pay for tax cuts. Unfortunately, the new federal deal does not fundamentally change the fiscal relationship between federal and provincial governments and support system transformation. This is a missed opportunity – and an area where much greater federal leadership is required.

Table 6: Canada Health Transfer, 2004/05 to 2019/20

Source: Government of Canada, 2019b; CIHI, 2022a.

Note: Provincial health expenditures are only available by calendar year.

Reducing wait times in Canada

Surgical wait times require urgent policy action. Although Canadian provinces have made some improvements over the last decade, surgical backlogs arising from the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic place greater urgency on provinces and the federal government to address timely access to surgical services.

This report assessed Canada’s mixed success in reducing wait times before and during the ongoing pandemic. It identifies seven major factors contributing to provinces’ wait time challenges:

- hospital capacity challenges that predate the COVID-19 pandemic;

- constrained access to seniors’ home and community care;

- privatization instead of public system improvement;

- limited government leadership to scale up public sector improvements;

- misalignment of specialist and surgeon payment with teamwork and system improvement;

- limited data collection and public reporting to support improvement and accountability; and,

- uncontrolled spread of SARS-CoV-2 placing ongoing strain on hospitals;

Canadian provinces have largely focused on short-term injections of funding – with an increased focus on outsourcing surgeries and medical imaging to for-profit clinics – rather than a sustained focus on system-level redesign and improvement. This report recommends that the federal government linking new and ongoing federal health funding to provinces’ phased implementation of the following evidence-based policy strategies:

- implementing single-entry models and improved waitlist management;

- improving operating room performance and acute care capacity;

- increasing access to public seniors’ home and community care; and,

- reducing inappropriate medical imaging and surgeries.

These strategies should be supported through a consistent pan-Canadian approach to health system learning and quality improvement, enabled by legislation and supported with the re-establishment of the Health Council of Canada. Health system learning and improvement should be modelled on the internationally recognized efforts in the Scottish National Health Service.

The success of Canada to improve timely access to surgeries depends on a new era of cooperative health care federalism, with federal and provincial leadership and collaboration. There is a clear need for increased and consistent federal health funding, but no longer can federal funding flow to provinces without strong accountability and policy implementation requirements.

Reducing wait times through a relentless commitment to system improvement must be the order of the day. Public health care is hanging in the balance.

[1] OECD, 2021.

[2] This excludes the dedicated federal funding for mental health and home care that was included in the 2016/17 bilateral agreements with the provinces.

[3] Canadian Health Coalition and Ontario Health Coalition, 2017.

[4] Institute for Fiscal Studies and Democracy, 2017.

[5] Canadian Health Coalition and Ontario Health Coalition, 2017.

[6] Government of Canada, 2022.

[7] Macdonald, forthcoming.

(Cover: Prime Minister Justin Trudeau chairs a working meeting on health care with the First Ministers of Canada’s provinces and territories February 7, 2023. Ottawa, Ontario. Photo by Adam Scotti, PMO)