“We don’t want it to catch on like wildfire,” says Health Canada on clinics charging patients

Health Canada officials responsible for monitoring provincial and territorial compliance with the Canada Health Act are concerned about increased reports of private, for-profit clinics charging patients for procedures covered by provincial health plans.

Officials from the Canada Health Act Division of Health Canada said that such practices are outside provisions of the Act, and that a new interpretation letter from the Health Minister is expected soon to provide greater clarity to the provinces and territories.

The remarks came during the kick-off of the Canada Health Act at 40 Research Roundtable at the University of Ottawa on June 20. Health Canada representatives delivered a presentation on their department’s Canada Health Act Annual Report. This year’s 400-page report, tabled on February 15, 2024, describes how the provinces and territories are faring when it comes to meeting the requirements of the Canada Health Act. The panel is now available for viewing here:

In the panel moderated by Hill Times health reporter Tessie Sanci, Jennifer Goodyer, Executive Director of the Canada Health Act Division for Health Canada, remarked, “there is still lots of life left in the Canada Health Act.”

Goodyer reminded the audience that the Canada Health Act is an example of federal spending power being used to set national standards in an area of provincial and territorial jurisdiction and that is why the Act’s principles are intentionally broad.

“The Canada Health Transfer is often characterized as an unconditional transfer to the provinces and territories, but it is not. It is clearly connected to the Canada Health Act and respecting [the Act’s] criteria and conditions,” said Goodyer.

Goodyer continued, “technically the Canada Health Act is a voluntary thing. The provinces and territories could choose to not adhere to the criteria and conditions [of the Canada Health Act], but if they did so, they would risk forfeiting some to and up to all of the Canada Health Transfer.”

The Health Canada presentation highlighted New Brunswick’s regulation restricting Medicare-funded procedural abortions to hospital settings as an example of a province not meeting the criteria and conditions of the Canada Health Act. Clinic 554 closed in early 2024, citing the government restriction as the key reason why the clinic was not financially viable.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau recently highlighted New Brunswick’s inadequate access to abortion services when visiting Liberal MLA Isabelle Thériault’s riding in Caraquet, New Brunswick in May. As reported by CBC, Trudeau said, “The shutting down of health and reproductive services offered by Clinic 554, the unwillingness to engage in allowing women to actually choose what happens to their future and their bodies is a disgrace.”

Trudeau used the occasion to promote the new pharmacare plan that will cover contraceptives. “Because it’s not right that women have to pay upfront to be able to have the choice to start a family or not, that’s why IUDs, the pill, all those things will be available for free to women as we move forward on pharmacare for prescription contraceptives,” Trudeau told CBC.

In late 2020, Thériault introduced an unsuccessful motion urging the government of New Brunswick to remove the regulation that blocks doctors in New Brunswick from being paid for performing abortion services outside a hospital setting, and to fund the services provided by Clinic 554.

Clinic 554, like the Morgentaler Clinic before it, made it a practice to never turn away anyone in need of an abortion, but it meant constant financial turmoil for the clinics, ultimately leading to the end of procedural abortion services at Clinic 554 in early 2024.

Reproductive Justice Access Now NB, a research project funded by Health Canada, in their report estimated that between 2015 to 2022, Clinic 554 paid $52,245 in pro bono services to patients, paying on average $439.03 for each patient who needed financial assistance.

Provinces can reverse their deductions if they remedy violations to the criteria and conditions of the Canada Health Act, but in the case of abortion access in New Brunswick, the province refuses to budge.

Goodyer noted that New Brunswick has been taking those deductions for years and that “they have been clear that they will not be changing that regulation. They think they have enough access to abortion through their hospitals.”

The research roundtable audience heard that much of Health Canada Annual Report consists of provinces and territories describing their public health care insurance systems, and how these systems meet the Act’s requirements or go beyond them. For example, provinces and territories offer varying coverage for additional services that do not fall under the Canada Health Act such as dental care and physiotherapy.

The second half of the Health Canada presentation focused on the Annual Report’s section on debunking the myths associated with the Canada Health Act.

Goodyer first dispelled the myth that all health care in Canada must be publicly delivered. She clarified that the Act does not forbid the provision of health services by private companies, as long as the resident is not charged for insured health services.

“Private delivery is not contrary to the Canada Health Act. What is contrary to the Canada Health Act is private payment, so there is a difference,” said Goodyer.

Joining Goodyer was Lee Whitman, Assistant Director of Compliance and Interpretation at Health Canada. Whitman debunk the myth that one can use their health insurance card to get on a shorter waitlist in another province or territory. While the principle of portability found in the Canada Health Act means that Canadian residents are covered for insured emergency health services during temporary absences from their home province or territory, Whitman noted that residents must get prior approval for non-emergency services in another province or territory.

According to the Health Canada presentation, the Canada Health Act is a relatively short piece of legislation and does not include a list of medically covered services. It is up to the provinces and territories in consultation with their medical professional associations to determine what is covered.

Whitman described how Health Canada monitors provincial and territorial health care systems for non-compliance through various public sources, noting that Health Canada relies on the cooperation of the provinces and territories as it has no investigatory powers under the Canada Health Act. When a concern of non-compliance arises, Health Canada asks the province or territory to investigate, the province or territory then reports its findings to Health Canada, the findings are then discussed, and officials work together to ensure the jurisdiction returns to compliance with the Act. Whitman and Goodyer reiterated that most issues are resolved among the officials.

Chapter 2 of the Health Canada report also addresses patient charges and outlines the deductions up to March 2023. Goodyer explained that in 2023, the first deductions under their new Diagnostic Services Policy, totalling over $76 million, were taken against the Canada Health Transfer payments of several provinces. This year’s report notes patients were charged for diagnostic services in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick Québec, Saskatchewan, Alberta and British Columbia.

Goodyer stressed that many of the provinces that took deductions for charging patients for diagnostic services have “taken steps to eliminate those charges to crowd out the private payment and also while improving access to their residents as well.”

“British Columbia purchased a number of those private clinics and then rolled them into their public system, and they have also sent cease and desist letters to the clinics that are providing for insured services to not charge for any medically necessary diagnostic scans in their clinics,” explained Goodyer. Manitoba has also fully eliminated patient charges for diagnostic services.

The Health Canada presentation also noted that deductions of the Canada Health Transfer occurred for patient charges for surgical abortion services in New Brunswick and Ontario, patient charges for surgical services in British Columbia, and patient charges for cataract services in Newfoundland and Labrador.

According to Whitman, a reimbursement policy implemented in 2018 has led to provinces being reimbursed more than $175 million after they corrected the reasons for their deductions. Provinces and territories have up to two years to implement corrective actions such as bringing private clinics into the public system, prohibiting patient charges by these clinics, and enforcing these prohibitions to ensure patients are not facing financial barriers to accessing care.

The audience heard that Health Canada is building on the foundation of Canada Health Act with the expansion of access to services that currently fall outside the Act’s basket of insured services, including increased transfers to provinces and territories to support mental health and addictions services, expansion of dental care, and plans for pharmacare and national long-term care standards.

“Health Canada thinks that if there is an innovation in health care delivery, it should be to the benefit of all Canadians, not just those who can afford to pay for those innovations.”

Jennifer Goodyer, Health Canada

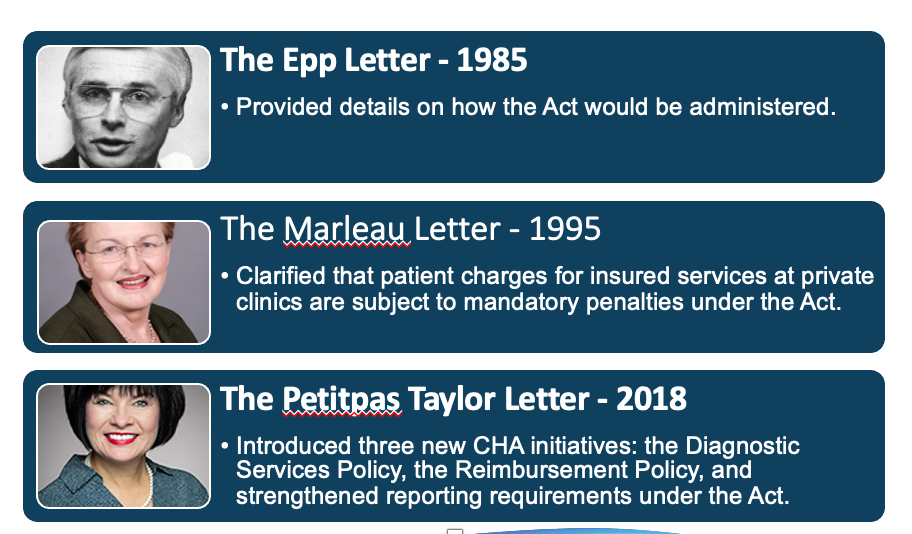

Goodyer noted several federal health ministers have issued clarifications of the Canada Health Act’s intent and application through interpretation letters to the provincial and territories. From the Health Canada presentation:

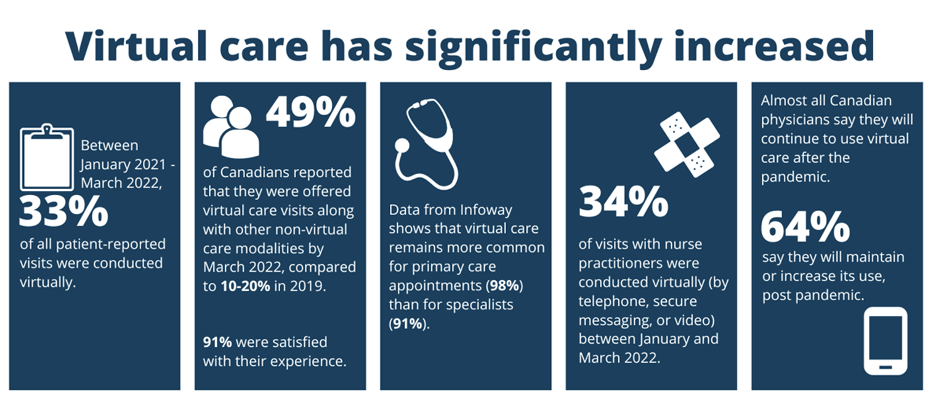

Goodyer also explained how technological advancement have changed how care is delivered. Goodyer noted that virtual care has the potential to improve access to both primary and specialist care. However, she cautioned that such advances are resulting in charges to patients for services that would be considered insured if provided in-person by a physician.

From the Health Canada presentation –

The landscape of health care is also changing with more regulated health care professionals, such as nurse practitioners and pharmacists, delivering services once only provided by physicians.

Goodyer expressed that while such developments can increase access to care, they are also resulting in charges to patients for medically necessary services.

“Health Canada thinks that if there is an innovation in health care delivery, it should be to the benefit of all Canadians, not just those who can afford to pay for those innovations,” said Goodyer.

Tessie Sanci asked the Health Canada staff about private providers getting away with charging for medically insured services. Whitman responded that “operators of private clinics are becoming increasingly savvy about navigating health care legislation that does not put them off-side.”

Whitman used the example of the B.C. government that intervened when a private clinic was charging a subscription fee. B.C. told the clinic that people cannot pay to receive expediated physician care. That clinic then pivoted to using nurse practitioners that up to this point in time has not been captured under the Canada Health Act interpretation.

Sanci then asked about the reluctance to amend the Canada Health Act. Whitman argued that the Act is the foundation, but not the ceiling of what provinces and territories can provide in health care. Goodyer added that there is “a risk of losing what we have.” Instead of amending the Canada Health Act, Goodyer said “sister legislation, which would mirror the principles and good components of the Canada Health Act,” should be considered for other areas of health care.

From the audience, Kevin Skerrett, with the Ottawa Health Coalition, which is affiliated with the Ontario Health Coalition, shared the story of the South Keyes Health Center in Ottawa. The walk-in clinic introduced a $400/year subscription fee last October to people wanting access to a nurse practitioner that would provide prescriptions and other family physician services.

“We interpret this to be a violation of the CHA and the Ontario equivalent statute,” said Skerrett. “This is an insured service and charging for it, regardless of who is providing it, is a violation… This could catch on like wildfire if we do not put a stop to it.”

“We don’t want it to catch on like wildfire,” said Goodyer in response. “That is why successive ministers have said they have significant concerns about the practice of nurse practitioners charging for services that would indeed be covered if provided by a physician.”

Goodyer noted that an interpretation letter is coming out soon from federal health minister to stop the entrenchment of such practices.

This is the first of a series of eight weekly blogs summarizing what was heard at the Canada Health Act at 40 Research Roundtable at the Unvirsity of Ottawa on June 20, 2024. Next week’s blog will discuss the Creeping Privatization panel with Andrew Longhurst, Parkland Institute’s Rebecca Graff-McRae and Canadian Doctors for Medicare’s Dr. Danyaal Raza and Dr. Sheryl Spithoff.

Tracy Glynn is the National Director of Projects and Operations for the Canadian Health Coalition