Governments should adopt a vaccines-plus strategy for COVID-19, part VII

This is the seventh part of a series examining the policy barriers and solutions to reducing surgical wait times in Canada. The series has been adapted from a research paper by Andrew Longhurst. The complete paper with reference list for the footnotes is available here.

Finally, the ongoing pandemic and the removal of public health protections in most provinces means that SARS-CoV-2 transmission is uncontrolled in most provinces, resulting in a “variant soup” with consistently high levels of transmission. Despite many provinces restricting lab-based PCR testing for the general population, wastewater surveillance (showing the concentration of virus in sewage) and COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths indicate that the pandemic is not over.

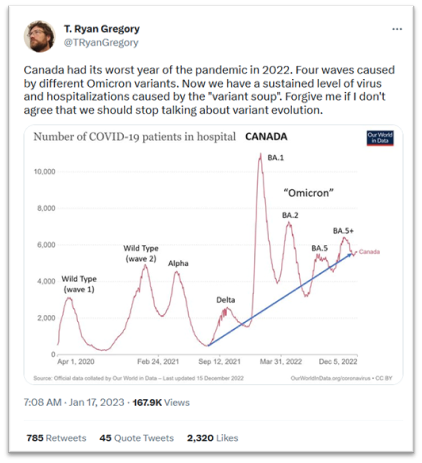

With low vaccination rates in much of the global South and unmitigated transmission, the virus continues to mutate with the emergence of new variants that evade immunity from prior infection and vaccination. We continue to see cycles of increased hospitalizations and hospital strain, resulting in cancelled surgeries and delays in scheduled care. As evolutionary biologist T. Ryan Gregory reminds us (see right), 2022 was the worst year of the pandemic for hospitalizations (and deaths) and pressure on acute care services continues to increase from 2020. Canadian provinces will continue to struggle with maintaining timely access to surgeries without the strategic use of public health interventions to reduce and control viral transmission.[1]

Provinces and federal government should adopt a vaccines-plus strategy

Even with the emergence of more transmissible – and potentially virulent – variants, provinces will be in a much better place to prevent surgery cancellations and backlogs if provinces adopt a “vaccines-plus” strategy.[2] A vaccine-plus policy strategy involves acknowledging SARS-CoV-2 is an airborne virus and educating the public and implementing measures that reflect scientific understanding:

SARS-CoV-2 is airborne. There is scientific consensus that the primary transmission mode of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, is through tiny aerosols that float in the air like cigarette smoke.[3] These aerosols can reach dangerous concentrations especially in poorly ventilated spaces. Most provincial public health authorities have not clearly communicated and educated the public on the airborne nature of transmission as evident by the focus in many businesses and public settings on handwashing and cleaning surfaces.

Set public indoor air-quality standards. As an airborne virus, improving ventilation in schools, hospitals and long-term care, workplaces and other congregate settings should be a priority.[4] Provinces, including BC, have been reluctant to set any standards or mandate mechanical ventilation improvements in higher-risk settings such as schools. It is also a matter of occupational health and safety: employers must take reasonable steps to prevent workers from workplace-acquired infections from infectious diseases. Canadian provinces can look to jurisdictions like Belgium that have started regulating indoor air quality in public places and requiring public display of C02 monitoring.[5] Government regulates pollution and outdoor air; governments need to improve indoor air quality in an effort to prevent disease and protect our health system. Specific measures include the following:

- In spaces with limited or poor mechanical ventilation, portable HEPA units should be used to improve filtration.

- Monitoring ventilation with proxy measures like CO2 monitors and keeping levels below 800 parts per million is important.

Use tight-fitting masks and respirators in higher-risk indoor places. Tight-fitting, high-quality masks and respirators prevent us from inhaling aerosols.[6] We need to urgently set mask standards in public spaces, educate the public about the importance of high-quality respirators, and provide workers and low-income people with high-quality respirators.

Increase access to, and provide guidance on, testing. Rapid tests are an effective public-health tool and can quickly identify infectious individuals and help prevent onward transmission. Provision of rapid antigen tests free to the general population. This should continue. PCR tests, while providing higher sensitivity, are a confirmatory diagnostic tool. Both types of testing are the basis for a comprehensive and publicly funded testing approach that will help us reduce spread and protect our health system’s capacity to delivery timely surgical and diagnostic services.

Require 10-day isolation for positive cases and provide at least 10 days paid sick leave. Evidence shows that most people remain infectious for at least ten days.[7] However, most provinces do not provide legislated paid sick leave. BC’s five days of paid sick leave is the most generous in the country, but falls short of the minimum ten days called for by health experts and economists.[8]

Stay up-to-date with current vaccinations that protect against severe disease and death. As current vaccines offer limited protection against infection and Long COVID, vaccines should be used in combination with the above measures intended to prevent transmission in the first place.

[1] Karan, 2022.

[2] Greenhalgh et al., 2022.

[3] Greenhalgh et al., 2021.

[4] Greenhalgh et al., 2021.

[5] Chini, 2022.

[6] Greenhalgh et al., 2021.

[7] Adam, 2022.

[8] Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives—BC Office, 2022.